How Solenoid Valves Work in High-Pressure Industrial Systems (Engineer’s Guide)

13.01.2026

Having worked in industrial automation for over fifteen years, I've learned one important lesson: pressure isn't a number on a gauge; it's energy, always seeking a weak spot. When you design a system for 5-10 bar, you're operating in a "comfort zone." But cross the threshold of 40, 100, or even 400 bars, and these familiar rules no longer apply.

In this article, we'll take a deep dive into how solenoid valves work under extreme loads. We won't limit ourselves to catalog theory. My goal is to give you an understanding of how hardware behaves in the factory when valves are subjected to enormous stress and coils are operating at their thermal limits.

I invite you to consider:

- How solenoid valves control flow under high pressure;

- Why does valve design change when pressure increases;

- Direct-acting vs pilot-operated valves explained clearly;

- Real-world examples from pneumatic and hydraulic systems;

- Diagrams, failure cases, and a selection checklist.

Why High Pressure Changes Everything for Solenoid Valves

When discussing "high pressure," it's essential to distinguish between the various environments. In systems using a pneumatic solenoid valve, pressures between 16 and 40 bar are considered high (for example, in PET blow molding lines). In hydraulics, these numbers are just the beginning.

Why does the usual valve selection logic break down as pressure increases?

- Seat load. At 100 bar, even a tiny 5 mm orifice experiences a load of approximately 20 kg. The seal is literally "pressed" into the metal seat;

- Flow velocity and erosion. When the valve opens, the fluid is forced through a narrow gap at incredible speed. If the fluid contains even microscopic particles, they act as an abrasive cutting tool, destroying the valve edge;

- Increased friction. All moving parts – plungers, rods, rings– are pressed against the walls with greater force under pressure. This requires a greater starting force from the coil.

If you attempt to use a standard valve where a specialized high-pressure solenoid valve is required, you will encounter a situation where the coil will hum but cannot move the stem, or the valve will begin to leak after a couple of days due to deformation of the soft seals.

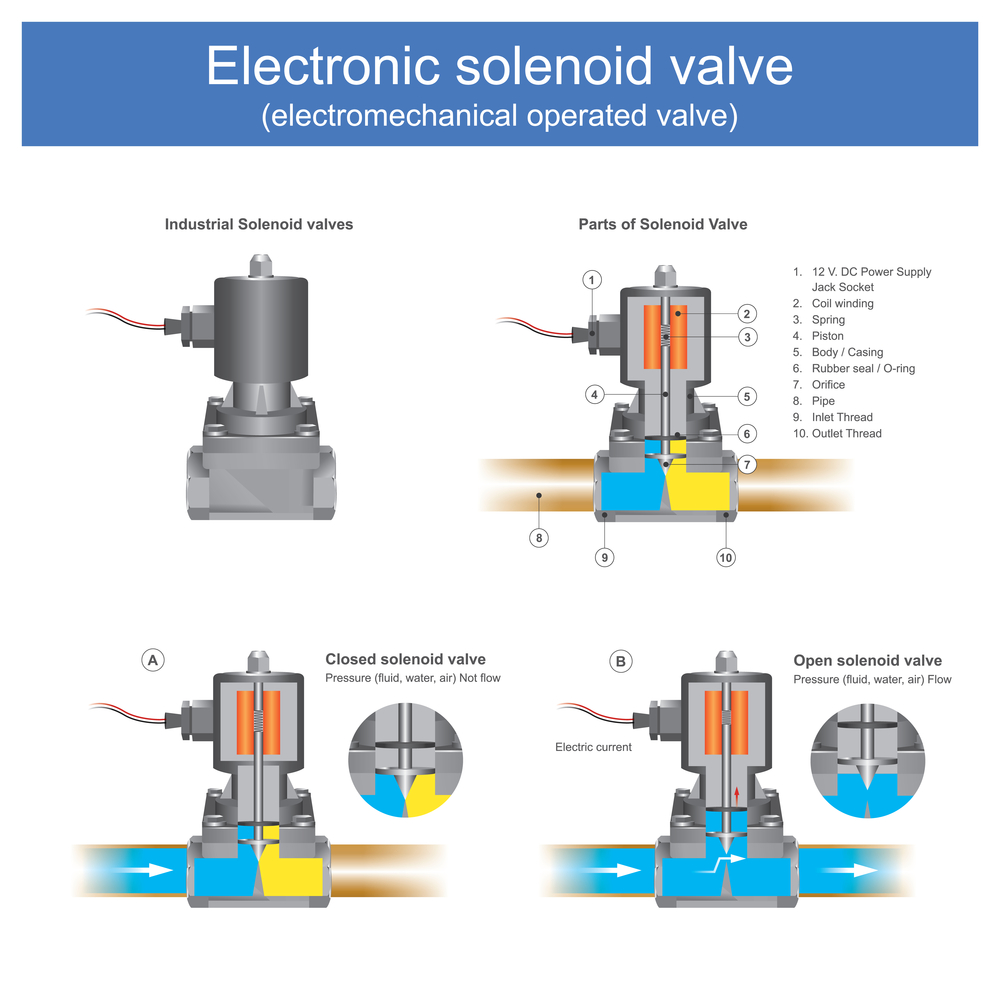

Basic Solenoid Valve Working Principle (Quick Refresher)

Let's quickly review the basics. Any solenoid valve is an electromechanical device. The solenoid valve working principle is based on the use of an electromagnetic coil to create linear motion.

Main components:

- Coil. A copper winding that creates a magnetic field when current is applied;

- Plunger. A ferromagnetic core that moves within a tube;

- Seal. A material (rubber, plastic, or metal) that blocks flow;

- Spring. Returns the plunger to its original position when the voltage is removed.

In high-pressure systems, each of these components is modified. Springs become stiffer, magnetic gaps become more precise, and coils become more powerful to overcome fluid resistance.

How Solenoid Valves Operate Under High Pressure

When operating under load, the key concept is "force balance". For the valve to open, the magnetic field force must be greater than the sum of the pressure force and the spring force.

This explains why we can't simply install a huge coil for high pressure valve control. There is a physical limit to the saturation of the magnetic circuit. This is where engineers begin to look for workarounds: either reducing the orifice area (direct action) or using the energy of the medium itself (pilot control).

At high pressures, surface finish is also critical. The slightest roughness on the stem at 200 bar will cause a leak that cannot be stopped by tightening the bolts.

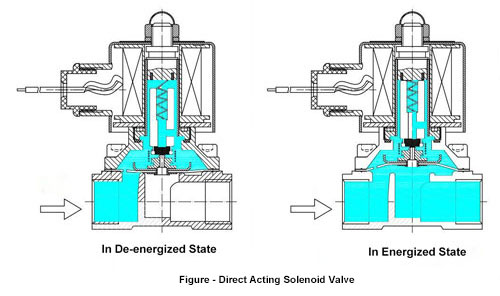

Direct-Acting Solenoid Valves in High-Pressure Systems

In direct-acting valves, the solenoid is rigidly connected to the seal. When energized, the plunger simply lifts the valve, overcoming all line pressure.

High-pressure operation features:

- Flow limitation. For the coil to lift the valve at 100 bar, the orifice diameter (orifice) must be very small – typically 0.5 to 1.5 mm;

- Independence from pressure. This is a huge advantage. If the pressure in your system can drop to zero (for example, when emptying a tank), only a direct actuator guarantees opening;

- Application. I often use them as "pilots" for larger valves or in precision reagent dosing systems, where the injection volume is minimal, and the hydraulic solenoid valve must act instantly.

Pilot-Operated Solenoid Valves in High-Pressure Systems

This is the "heavy artillery" of automation. Here, the solenoid controls not the main flow, but a small bypass channel. The main valve (usually a piston) is moved by the pressure difference.

Why are they so prevalent in heavy-duty systems? Because they allow for the control of a 50 mm diameter pipe at 40 bar using the same coil that, in direct action, would barely cope with the eye of a needle.

But there's a catch: they require a "back pressure." If the valve outlet pressure equals the inlet pressure (for example, if there's a large, empty pipe downstream of the valve), the piston may not rise. I've seen dozens of cases where, during commissioning, engineers complained about a "defective" valve that simply couldn't open without a minimum differential pressure.

Direct Acting vs Pilot Operated – High-Pressure Comparison

For clarity, I have prepared a table that will help you quickly navigate your choice.

Feature | Direct Acting | Pilot Operated |

Max pressure capability | Limited | High |

Flow capacity | Low–medium | High |

Power consumption | Higher | Lower |

Pressure required | None | Minimum required |

Typical use | Precise control | Large flow systems |

This is a basic direct acting vs pilot operated solenoid valve guide that should be hanging on every designer's wall.

Common Problems in High-Pressure Solenoid Valve Installations

At high pressure, problems manifest quickly and dramatically. Here's what I encounter most often:

- The valve doesn't open. The system pressure is higher than the solenoid valve pressure rating specified in the datasheet. The coil simply doesn't have enough force to overcome the liquid column;

- Chattering. The valve opens and closes quickly. This often happens with pilot valves if the flow rate through them is too low. The piston can't lock in the up position and "floats";

- Burned coils. If the plunger is jammed with dirt in the intermediate position, the alternating current in the coil doesn't drop to the operating value (holding current), and it overheats;

- Seal erosion. "Star disease" of high-pressure valves. A stream of fluid at a small opening cuts a groove in the soft seat, after which the valve loses its seal.

Materials and Sealing – What Matters at High Pressure

The choice of material isn't a matter of taste, but rather a matter of the survival of your equipment:

- Brass. Good up to 40-60 bar in non-aggressive environments. Above that, there's a risk of zinc leaching and weakening the housing;

- Stainless steel. The standard for high pressure. Withstands up to 400+ bar and is chemically inert;

- NBR. Forget about it above 20 bars unless it's a special compound;

- FKM. Doesn't swell with oil and maintains a perfect seat seal even under extreme pressure;

- PTFE (Teflon). The king of high pressure. Doesn't deform, is slippery, and maintains temperature;

- Metal-to-metal. Used in extreme conditions where any rubber would turn to dust.

If you are installing an industrial solenoid valve on high-pressure steam, make sure that the seals not only "hold temperature" but are also not subject to a "steam explosion" (when microbubbles of steam inside the rubber expand when the pressure is released and rupture it).

Real-World Applications I See Most Often

Let's look at some real-world examples:

- Hydraulic power units (HPU). In high-power hydraulic power units powering presses or lifts, each hydraulic solenoid valve operates under extreme loads. These valves control oil flows under pressures of up to 350 bar. Resistance to dynamic shocks and compatibility with aggressive additives in hydraulic fluids are crucial factors;

- Compressed air manifolds. PET blow molding lines or marine diesel starting systems use high-pressure pneumatic solenoid valves. Response speed is critical here – the valve must open within milliseconds to deliver a precise amount of air at 40 bar;

- Steam and thermal oil systems. In these systems, pressure goes hand in hand with high temperatures. Regular rubber would crumble to dust, so we use valves with PTFE or metal-to-metal seals to control steam and thermal oil;

- Chemical dosing and injection skids. Chemical injection systems for oil wells or chemical reactors require very precise high-pressure valve control. These are often small, direct-acting valves that must withstand corrosion and maintain tightness at pressures exceeding 150 bar.

How to Choose the Right Solenoid Valve for High Pressure

To avoid ordering errors, use this solenoid valve selection guide:

- Define maximum operating pressure and safety margin. Never choose a device that's too tight. If your operating pressure is 100 bar, look for a solenoid valve pressure rating of at least 125–130 bar. This pressure margin protects you from accidental surges and water hammer;

- Identify fluid type and temperature. Steam, nitrogen, aggressive chemicals, or mineral oil? As I mentioned, for oil and chemicals under pressure, I always use FKM – it doesn't swell and maintains seat geometry;

- Decipher direct-acting vs. pilot-operated. If your system can operate with a pressure drop close to zero, choose a direct-acting actuator. If you need to control high flow on the main line and you always have a minimum back pressure (0.5+ bar), choose a pilot-operated actuator;

- Verify flow rate and orifice size. Don't rely solely on the pipe thread. Check the Kv value. An orifice that is too small will cause cavitation and noise at high pressure, while one that is too wide may fail to open due to insufficient coil power;

- Check coil voltage, duty cycle, and power limits. Coils run hotter at high pressure. If the valve must be open 24/7, ensure it is rated for 100% duty cycle (ED);

- Confirm certifications and safety requirements. For hazardous areas (ATEX) or high-pressure systems subject to technical regulations, safety certifications are mandatory.

Installation Tips That Prevent Failures

Installation is an art:

- Orientation and mounting direction. Install the valve with the coil facing up to prevent the accumulation of sludge and dirt inside the plunger guide tube. Failure to do so often leads to rapid mechanical wear and seizure of the valve's moving parts;

- Importance of upstream filtration. At high pressure, even a tiny grain of sand turns into a projectile, capable of instantly destroying the polished seat surface. Always install a filter with a mesh size of no more than 100 microns upstream of the high-pressure solenoid valve;

- Why grounding and surge protection matter. Use high-quality grounding and surge protection to prevent burnout of the coil windings. This is especially important for high-power inductive loads, which create significant interference in the control circuits during switching;

- Commissioning checks before full-pressure operation. Before applying a full load, test the solenoid valve operating principle at low pressure to ensure all joints are tight. Gradual commissioning allows for the timely detection of installation defects and the prevention of seal failure.

Final Advice from the Field

The key to a valve's long life is stability. Pressure alone rarely kills a valve; sudden surges, overheating, and dirt do. If you feel like your budget allows you to skimp on a brand but not a good filter, you're making a mistake. In my experience, even a mid-priced valve has worked for years if the environment was clean and the voltage was stable.

FAQs About High-Pressure Solenoid Valves

1. Can a standard solenoid valve handle high pressure?

In theory, it can, as long as the materials are compatible. In practice, oil has higher friction and the risk of hydraulic shock, so it's better to use a specialized hydraulic solenoid valve.

2. Why does my pilot valve fail at startup?

This is normal (up to 80-90 C), but if you're having trouble, check the voltage. If it's 10% below normal, the current increases, and the coil burns out.

3. Is higher pressure always better for pilot valves?

A characteristic whistling sound will appear when the valve is closed, or a slow drop in system pressure will occur after stopping.

4. How do I size a solenoid valve correctly?

Operating control circuits at 24V DC is an industry safety standard. A coil failure at 220V AC in a damp environment can lead to serious safety risks.

5. What's the most common cause of coil burnout?

Yes, very severely. Thick oil slows the plunger's movement, which can lead to coil overheating.